If you want to do a deep dive on child well-being in Rhode Island, we urge you to check out the 2020 RI Kids Count Factbook. It’s a great resource of data that informed this post.

There’s a group we may not think of when we talk about housing discrimination: kids. A study in 2002 showed that only 38% of respondents knew that it was illegal to discriminate against families when they’re looking for homes (Harvard 2013).

Housing stability and conditions are directly linked to childhood development. Housing is health. Housing is education. A look at court-ordered eviction records shows that neighborhoods with larger percentages of children experience more evictions. A 1% increase in the percentage of children generally increases that neighborhood’s eviction rate by 6.5 percent. Households with children are 17% more likely to receive and eviction judgement than households without children (Harvard 2013).

Compared to other states, Rhode Island kids are hit hard. Rhode Island invests only one-fifth per-capita what neighboring Massachusetts does in affordable housing. Between 2013 and 2018, Rhode Island saw average cost of a single family home rise 22% (RI Kids Count 2020). The quality of housing correlates with lower kindergarten readiness scores. Those scores are worse if the child’s house is in foreclosure, in tax delinquency, or if it is owned by a speculator (Housing Matters 2019).

In 2019, 579 (2%) of the 23,947 Rhode Island children under age six who were screened had confirmed elevated blood lead levels of ≥5 µg/dL. Children living in the four core cities (4%) were four times as likely as children in the remainder of the state (1%) to have confirmed elevated blood lead levels of ≥5 µg/dL. (RI Kids Count 2020)

For Rhode Island’s high schools in the Class of 2019, the graduation rate was 65% for homeless students and 84% for non-homeless students. And 25% of homeless students met expectations on the third grade Rhode Island Comprehensive Assessment System (RICAS) English language arts assessment compared to 48% of non-homeless students (RI Kids Count2020).

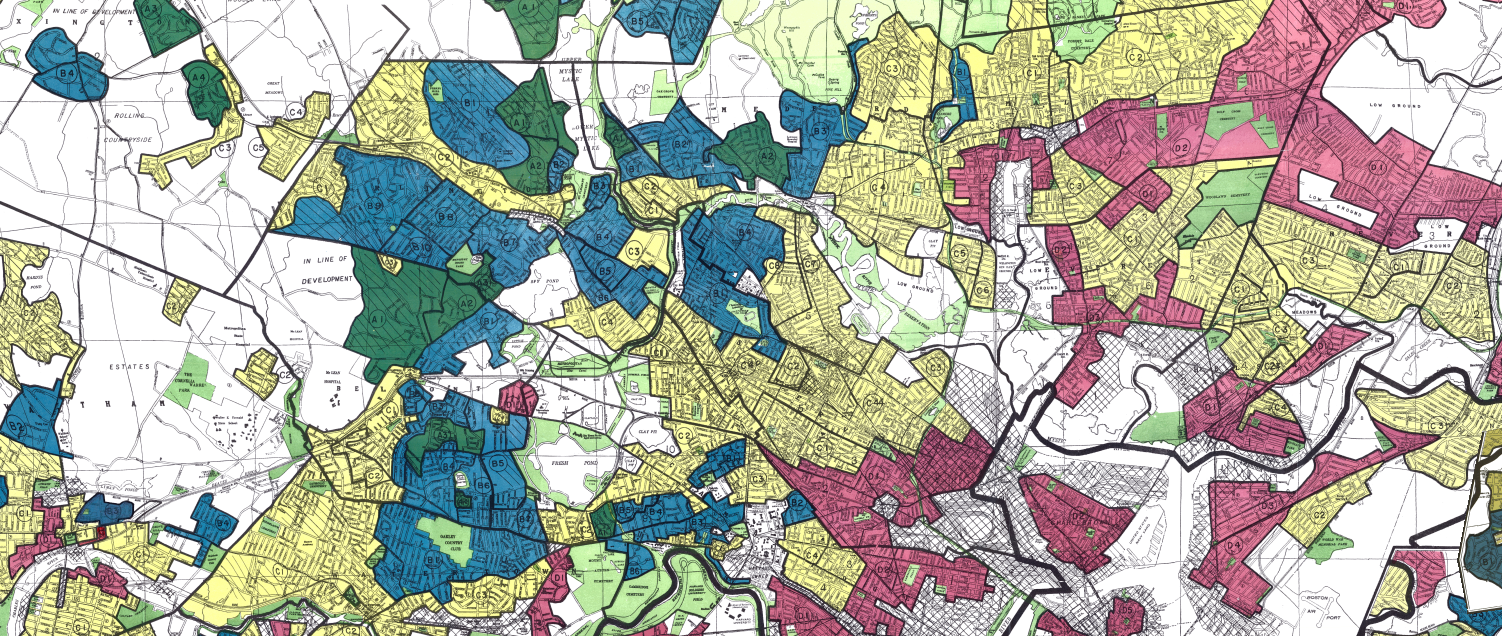

In 1954, the case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka established that any law that established segregation in schools was unconstitutional. But segregation persists. A study in 2016 found that half of schools in the US were more than 75% white or 75% nonwhite. (New York Times 2019) And because funding for schools is still tied to local taxes, a starkly unequal system is created for children and teachers.

The most dramatic impacts are on homeless children. In the United States each year, one in 30 children are homeless. That’s 2.5 million children who experience homelessness each year. According to Rhode Island Kids Count 2020 Factbook, “in 2019, 279 families with 603 children stayed at an emergency homeless shelters, domestic violence shelters, or transitional housing facility in Rhode Island. Children made up 21% of the people who used emergency homeless shelters, domestic violence shelters, and transitional housing in 2019. Nearly half (44%) of these children were under age five.” (RI Kids Count 2020)

Evidence shows that investments in housing have dramatic effects on child development and educational outcomes. That’s why we need long-term sustained investment in the production of affordable homes. Community revitalization efforts in public housing improve math and reading scores of elementary school students (Housing Matters 2018). Children who live in HUD–assisted households have half the prevalence of elevated blood lead levels than children in non-assisted low-income families (Housing Matters 2019).

RESEARCH

Evicting Children | Harvard | Matthew Desmond 2013

When Renters Move, What Factors Affect Student Test Scores? | Housing Matters | Sarah A. Cordes April 01, 2020

2020 Rhode Island Kids Count Factbook | Kids Count RI | 2020

Stable Housing Can Launch Youth Leaving Foster Care on a Path to Success | Housing Matters | Maya Brennan June 19, 2019

How Housing Affects Children’s Outcomes | Housing Matters | Veronica Gaitán January 02, 2019

Community Revitalization Efforts Can Improve Public School Performance | Housing Matters | Donna Comrie July 25, 2018

Late Rent Payments Can Harm Health Outcomes of Caregivers and Children | Housing Matters | Megan Sandel February 01, 2018

STATS

After moving, students experienced a negative effect on math scores in both the short term and the long term. | Housing Matters 2020

An analysis of court-ordered eviction records to demon-strate that neighborhoods with larger percentages of children experience higher evictions. All else equal, a 1 percent increase in the percentage of children is predicted to increase a neighborhood’s evictions by 6.5 percent. | Harvard 2013

On average, the probability of a household with children to receive an eviction judgment is about 17% higher than that of a household without children. | Harvard 2013

When in 1980 HUD commissioned a nationwide study to assess the magni-tude of the problem, researchers found that “only one quarter of rental housing units [were] available to families with children with no restrictions. | Harvard 2013

In 2009, 20 percent of all HUD complaints alleged discrimination based on family status. | HUD 2010

Unlike discrimination based on race or gender, discrimination against fami-lies and children often is not even recognized as discrimination. A report based on a nationwide sample of Americans found that the majority of respondents recognized discrimination based on race, religion and ability to be illegal, but only 38 percent were “aware that it is illegal to treat households with children differently from households without children”. | Harvard 2013

Between 2014 and 2018, in Rhode Island, the median family income for married two-parent families ($105,323) was more than twice that of male-headed single-parent families ($45,491) and more than three and a half times that of female headed single-parent families ($28,585). | Kids Count RI 2020

While Rhode Island’s unemployment rate has declined, many workers remain unable to find full-time employment and struggle to make ends meet with inadequate and unpredictable income. As of 2016, almost 24 million people in the U.S. worked in low-wage jobs where they were paid $11.50 per hour or less. | Kids Count RI 2020

In Rhode Island over the past few decades, income inequality has grown. In 2015, the top 1% ($928,204) of Rhode Island households had average incomes that were 18 times more than the bottom 99% ($50,963) of households. Rhode Island is ranked 32nd of the 50 states in income inequality based on the ratio of top 1% to bottom 99% income. | Kids Count RI 2020

In 2019, a worker would have to earn $31.75 an hour and work 40 hours a week year-round to be able to afford the average rent in Rhode Island without a cost burden. This hourly wage is more than three times the 2019 minimum wage of $10.50 per hour. | Kids Count RI 2020

2018 Rhode Island Standard of Need, it costs a single-parent family with two young children $55,115 a year to pay basic living expenses, including housing, food, health care, child care, transportation, and other miscellaneous items. This family would need an annual income of $62,844 to meet this budget without government subsidies. | Kids Count RI 2020

Between 2013 and 2018 the median cost of a single family home in Rhode Island rose 22%. While median wages only increased 13% in that time. | Kids Count RI 2020

In 2018m Rhode Island only invested 1/5 the per capita amount that Massachusetts does in affordable housing. | Kids Count RI 2020

Rhode Island law establishes a goal that 10% of every community’s housing stock qualify as Low- and Moderate-Income Housing. Currently, only six of Rhode Island’s 39 cities and towns meet that goal. | Kids Count RI 2020

In the United States, 2.5 million children (one in 30) are homeless each year. | Kids Count RI 2020

In 2019, 279 families with 603 children stayed at an emergency homeless shelter, domestic violence shelter, or transitional housing facility in Rhode Island. Children made up 21% of the people who used emergency homeless shelters, domestic violence shelters, and transitional housing in 2019. Nearly half (44%) of these children were under age five.| Kids Count RI 2020

In Rhode Island in 2019, 25% of homeless students met expectations on the third grade Rhode Island Comprehensive Assessment System (RICAS) English language arts assessment compared to 48% of non-homeless students. | Kids Count RI 2020

In Rhode Island, the four-year high school graduation rate for the Class of 2019 was 65% for homeless students and 84% for non-homeless students. | Kids Count RI 2020

Children who live in US Department of Housing and Urban Development–assisted households have half the prevalence of elevated blood lead levels than children in nonassisted low-income families, after adjustment for demographic, socioeconomic, and family characteristics. These data suggest that low-income families could see improved health benefits for their children either increased access to subsidized housing or increased lead remediation and regulations on existing unassisted housing. | Housing Matters 2019

Living in poor-quality housing and disadvantaged neighborhoods is associated with lower kindergarten readiness scores. Further, children living in homes that were in foreclosure, in tax delinquency, or owned by a speculator were more likely to receive worse kindergarten readiness scores than children in stable housing. | Housing Matters 2019

Evidence indicates that community revitalization efforts in public housing improve math and reading scores of elementary school students. | Housing Matters 2018

More than 40 percent of youth aging out of the child welfare system experience housing instability within two years of leaving foster care. | Housing Matters 2019